Aabijijiwan / Ukeyat yanalleh, The Water Flows Continuously

Aabijijiwan / Ukeyat yanalleh, The Water Flows Continuously

Karen Goulet and Monique Verdin

Winona, MN

Minnesota Marine Art Museum

January 27 - July 7, 2024

Aabijijiwan / Ukeyat yanalleh – translated into Ojibwe and Houma as, “The Water Flows Continuously” – is a collaborative exhibition from multimedia artists Karen Goulet (Ojibwe) and Monique Verdin (Houma). Karen and Monique are sisters of the same river, connected by the planetary lifeforce known as the Misi-ziibi (Big River, Ojibwe) near the headwaters in the north and remembered as Misha sipokni (Older than Time, Chata) in the coastal territories of the southern Delta, where the bayous of Turtle Island meet the sea.

The Misi-ziibi Misha siponi introduced Karen and Monique and encouraged their relationship to be immersed in the sacred systems of the watershed and the magic of the riparian zones. Aabijijiwan / Ukeyat yanalleh reflects their journeys together, up, and down river; illuminating diversities, connecting personal memories and curiosities, seasonal rituals and witnessing to the times of change recognized in the layers of Indigenous and colonial histories bound to the watershed they share.

“This exhibition reflects our shared love and gratitude for the Misi-ziibi Misha siponi. Our continuing journey was seeded in 2019 by the Big River Continuum. Through multimedia collaborations and explorations that mirror realizations, conversations, and contemplations found during our time together we continue to share stories of women and individuals from our lives and from our territories. It is an offering of love for our Misi-ziibi and the land and waters we call home.” – Karen Goulet and Monique Verdin.

Death Doulas

For most of history our pathway into this world has been through the hands of midwives and doulas. In the 21st century, these positions might have affiliations with hospitals, but that is actually a quite recent development. Midwives often receive more medical training regarding pregnancy, birth, and the postpartum period and doulas are more likely to be trained to provide you and your family with emotional, informational, and physical support during pregnancy, birth and the immediate postpartum period.

A Conversation with Susan Nesbitt

Story by Parker Forsell

Photograph by Dylan Overhouse

For most of history our pathway into this world has been through the hands of midwives and doulas. In the 21st century, these positions might have affiliations with hospitals, but that is actually a quite recent development. Midwives often receive more medical training regarding pregnancy, birth, and the postpartum period and doulas are more likely to be trained to provide you and your family with emotional, informational, and physical support during pregnancy, birth and the immediate postpartum period.

Major hospitals are developing birthing wings, which have been influenced by the fact that many women resist the sterile and fluorescent lit atmosphere of traditional medical establishments, and seek out home births or birth in a birthing center. Many midwives and doulas remain separate from hospitals, yet perform all the functions that would happen there. They will meet with expecting parents several times during a pregnancy, not only offering education on the baby’s development, but emotional support for the tremendous responsibility and gift it is to bring a human into the world. With the help of the midwife and doula a birthing plan is put together that includes medical considerations, but importantly an intentional plan for supporting the emotional and even spiritual comfort of the expecting mother, her baby and the family.

What about our pathway out of this world?

We can look to ancient cultures and see evidence of elaborate rituals based on beliefs held regarding the after-life. Many indigenous cultures talk of the path of souls and the spirit of loved ones traveling an invisible journey to star clusters and up through the milky way. There are considerations for the time of year that certain constellations are in a part of the sky - to the point of delaying burial or ceremonies until that time of year.

As we are coming to understand, many indigenous traditions are not something from the past, but in many instances are still being practiced today and have much to teach us.

Our European immigrant ancestors and for the most part current traditions, continue to follow a fairly similar path - preparation by a mortician after death, initiation of a wake where friends and family come together to pay respects, a funeral service (that many times involves a church pastor or minister), and then burial. There are many degrees of how this might be expressed spiritually, by the family and by those attending the event. Much of the tenor of the funeral is shaped by the family and loved ones and sometimes the one who has departed through a living will or conversations with friends and family.

Although the above may be the usual, there are many derivatives. In 2006, Susan Nesbitt and a group of women in the Viroqua, WI area founded Threshold Care Circle to help families rediscover the traditional folkways of a home vigil and family-directed funeral. The group also helped to found the Driftless Green Burial Alliance to educate and assist those interested in natural burial without traditional embalming fluids, and a simple wooden casket.

Nesbitt came to her life’s path through the experience of sitting with a dear friend at the end of their life. The experience was so moving for her Nesbitt says, “I knew deep in my bones that I wanted to do this again, that I wanted to be with people and their families during this sacred time.” At the time she knew nothing of death doulas, but found that one could become a hospice volunteer without a nursing degree. She has been a hospice volunteer for 20 years.

Henry Fersko-Weiss, author of Caring for the Dying: The Doula Approach to Meaningful Death, was a hospice nurse in New York City for six years and during that time he witnessed many patients dying under less-than-ideal conditions. Patients being rushed to the hospital to die, when they had specifically requested to die at home, a husband or wife sleeping through the death of their spouse in the next room because they were exhausted and did not recognize the signs of imminent death. There was something missing in the hospice program, the hospital could see it too, but the overall structure and caseload prevented them from being able to seek a solution.

In 2003, a friend of Fersko-Weiss decided to leave a PhD program in anthropology to become a birth doula. As he learned how she was working with people during their birth experience he began to wonder if the model might also work with those during the end-of-life journey. He ended up going through birth doula training to thoroughly understand the process.

After discussing his experiences with the CEO of the hospice he received her blessing to pilot a program of death doula training based upon what he had learned during the birth doula training. In 2004, 17 people enrolled in his program and became the first death doula’s in the country. Since then Fersko-Weiss has trained hundreds of others, over 2000 people have gone through his training to pursue the work of a death doula professionally or simply to help friends or family during their end-of-life journey.

Susan Nesbitt witnessed similar unevenness to the care she as a volunteer and the nurses were able to give within the structure of the hospice program. Though she says that hospice volunteers are doulas, a non-medical companion to the dying, there is further training for a doula. Nesbitt had been interested for a time in how she could become even more deeply involved in the hospice work, even contemplating being a nurse, social worker, or chaplain, but ultimately shied away from those roles because she felt that many times they did not get to spend much time with the person who was dying. In 2017, she first heard about death doulas, and ended up seeking out a doctor in La Crosse that had attended a training in Colorado. She recommended to her a program at the Conscious Dying Institute in Boulder, Colorado, and in 2019 she took the training to become a Sacred Passage Doula. Subsequently, Nesbitt went through a one year training in Oregon and is currently in her second year of apprenticeship.

Fersko-Weiss begins his book “Finding Peace at the End of Life”, by outlining the differing stories of a couple with the process of dying. The husband in the partnership had a precipitous, downward path caused by a tumor. Though they were working with a home health care nurse, one morning she came to find him unresponsive and immediately called 911. He was rushed to the nearest hospital, not his own, and slipped into a coma. After hours of sitting in a crowded waiting room the nurses encouraged his wife to go home and get some rest before her husband’s surgery the next morning. Her husband ended up dying alone, she actually found him herself when checking on him the next morning.

Understandably, the woman was greatly affected by the process and became determined to be more aware and in control of the process of her own end-of-life journey. When she found out she had ovarian cancer four years later she began work with a death doula.

An important part of the work with a doula involves working with your family and loved ones to discuss important life events, lessons learned, values they’d chosen to live by. An outcome of the process in this case had been to unpack a box she had been saving for years with cards and letters her husband and children had given her. They all took the time to read and discuss the memories the cards and letters brought up and her two children and a grandchild ended up making two large collages that put together pieces connected with the family. Fersko-Weiss writes, “the best part of this legacy work was the opportunity that she had to speak to her two children directly about the important values that had sustained and deepened her relationship to their father over the years.” The process helped her to let go of many of the negative memories that were associated with her lack of closure regarding her husband’s death.

Other activities that the doula worked with her on included guided imagery involving imagining a meaningful place from her life experience. The ability to become practiced in the process was meant to help bring a general sense of well-being and also a means to help alleviate discomfort associated with symptoms. The doula also worked with the family to discuss ways to bring a sense of the sacred into the space where she would die and a ritual that they would all do right after she passed.

“Death never takes a wise person by surprise” - Jean de La Fontaine

When it got close to the time of her passing one of her daughters had moved in, the doulas had established a schedule of round the clock shifts and the sacred space of the room had been prepared. She was surrounded by pictures, lavender scented candles were burning, family and friends were present. The doulas made sure her mouth and lips stayed moist, held her hand, caressed her face, and spoke to her of the special place that she had been envisioning during her guided imaginings.They were playing her favorite music and friends and family took turns reading quotes from the legacy collage that her children and grandchild made.

The process went on for three days with people spending time with her in shifts. When the doulas determined late one night that she was close to the end the children were called or awakened and both were able to be with her as she took her last breaths.

It might seem obvious, but one of the most important aspects of doula care is the ability to listen to a person experiencing their path to death. Fears, regrets, frustrations, struggling to understand a relationship with God or the afterlife - may be some of the whole-hearted and emotional concerns someone is needing to share. To be a deep and active listener, one has to leave a lot at the door, remain open and caring and conscious of inner dialogue that moves away from being able to really hear what someone has to say.

There are definitely parallels here with meditation or mindfulness, which lays a focus on letting the things go that take you away from being present. Centering is a technique that one can use to come into the present moment. It can involve focusing on the breath, taking some time, even 10-15 minutes, before visiting someone to simply pay attention to the breath. The simple act of taking the time to focus in this way can de-clutter the mind and aid in being able to truly be present and active in deeply listening to someone sharing the most important thoughts from their life.

Nesbitt mentions drawing from Parker Palmer’s Circle of Trust and the Touchstones that outline thoroughly how to participate as a deep active listener. She goes on to say that being present is so important for a doula, “I think all of us know what it feels like to be in the presence of a person who is really actually there. Listening without an agenda, with an open heart, non-judgmental. We are so often distracted that I feel it is the best I can offer, to just be present without any judgment.”

She also outlines that in deep active listening another key idea she has drawn from Palmer is that when the going gets tough, turn to wonder. “If someone is relating a really difficult story and I find myself dropping into a judgmental thought, I try to ask an open and honest question, rather than some thought that I feel I already have an answer to in my mind. To me active deep listening is being present, being in non-judgment, no fixing, no saving, no correcting, and turning to wonder. Also, importantly, being comfortable with silence.”

The practice of death doulas is so new that most people have never heard of it. Many of us live in fear of death or if we aren’t actively in fear, we have subconsciously pushed it off to a place where we don’t encounter the thoughts. In Nesbitt’s work she is frequently encountering family members who are meeting the idea for the first time and she has witnessed many who have been profoundly affected by the process. As part of her work with conscious dying she has been able to take many people and their families through a three month life review process. The work has even expanded beyond those that are actively dying to those that are deciding to participate in this process for their own preparation purposes.

The three month life review process addresses the question of having three months to live. What are the physical, spiritual, emotional, and practical levels of life? What are the areas of your life where you may have regrets, you wish things had gone differently, what things have been left unsaid, or what things do you still want to do. What would concrete steps look like right now? Nesbitt says, “the life review is really an opportunity for the dying person to reflect on their life in a profound way, but also to tie up loose ends and make amends when possible.”

Connected to the process can be a legacy project, visually pulling together pictures, stories, poems that have been influential in the life of a person and their family. Nesbitt says this can be a real gift to those that are left behind, “but it really helps people to see their gifts to the world, it may seem at first that some things are not that important, but most often it helps reveal to them their legacy. All of us have something to say and contribute.”

These projects also offer a chance for the dying person to experience how others have seen them as well. Nesbitt echoes, “it really gives the opportunity for all kinds of mysterious things to unfold.”

Another aspect of doula work includes the idea of vigil or some conscious participation in what those last days and possibly the days after death may entail. Nesbitt says there are two forms of vigil, the process of sitting with someone who is actively dying and the home funeral process that involves actively sitting with someone who has already died, praying in whatever way that might evolve. Whether before or after, the idea of vigil is to help with the transition. “It is being a companion, who is sitting and holding space. It doesn’t matter what the person’s beliefs are about the afterlife, religion or spirituality, the important part is that you are sitting there as a soul companion,” says Nesbitt.

As alluded to above, many cultures, ancient or current, connect ritual with the death transition. Nesbitt believes this is an extremely important part of the process, “it is a bit of a lost art, but I believe it absolutely helps with healing.” As a doula she tries to encourage people to incorporate ritual whenever possible, however that looks to them. Nesbitt remarks, “it does not need to be some elaborate, religious thing, it can be pretty basic, but it is showing up with intention.” She says she has seen the power of ritual play out in every single death journey she has shared.

Nesbitt relates a particularly powerful moment with a mother and sister of a recently deceased individual. Prior they both had shared that they did not want to see her after she died and they did not want anything to do with that process. Nesbitt shares, “we told them of the process of care of the body, that they could be included and it was a lovely way to cleanse the body, to prepare the body for the final destination.” They were open to the doula and volunteers doing this process, but they did not want to participate. It was taking place in a nursing home and the family was waiting in the hallway, but began to peek in to see what was going on. Because of their curiosity they were ultimately invited in and they ended up bathing the woman, their daughter/sister. Nesbitt says, “it was really beautiful and so profound and healing for them.”

Nesbitt adds that part of the work with the Threshold Care Circle is teaching how to bathe the body. She says, “it is actually incredibly intuitive, it’s in our bones, but we have given it all over to the funeral directors and we don’t know how to do it anymore.” Nesbitt remarks, it is just like when you take your baby home and think you don’t know how to wash a baby and have your first moment of insecurity. But you do it and then realize that you intuitively knew what to do. “It is the same thing with a dead body, you very lovingly wash the body and you can infuse that with as much ritual or ceremony as you want. There could be prayers, there could be music playing, the room could be decorated with flowers and wonderful smelling herbs. There can be an anointing of the body, with oil, blessing the head, and the eyes that have looked out onto the world, the nose that has smelled things and the mouth that said beautiful things.” The process can be made however the family wants, the doula can be doing these things for the family or they can be doing it together.

These rituals often can be part of the vigil process while one is actively dying and the family and their loved one may be very involved with how this will happen. Nesbitt notes a recent family she worked with that really took up this process, praying and singing during those final days with their loved one. The singing and praying continued during the washing of the body and others came when they were finally carrying the gentleman out of the nursing home and joined in the singing as they carried him out.

The body was wrapped in a special blanket for transporting him home where people sat vigil with him for four days around the clock, praying and reading, helping with the transition. Nesbitt stresses how all of this ritual can be very important for the healing process.

While this stands out, the idea of ritual tends to be taken up by individuals in quite a natural way. She says she can bring suggestions or examples of what others have done, and importantly assure people that they will not do anything wrong, but Nesbitt adds, “If you put your heart into this it will be beautiful, it will be meaningful.”

If one has the opportunity to be part of this process with their loved ones at the end of life, Nesbitt also stresses the very practical component of having things in order. It becomes a gift to those that are left behind to have things spelled out, things as mundane as passwords and other household directives. She works with people who are not diagnosed in any way yet as well, but want to be prepared. “Planning for death and talking about death does not need to be morbid,” Nebitt adds, “it really is something that our culture does not like to do.” She feels bringing death out of the closet and talking about it is part of being grateful for being alive, while also being conscious of what is inevitably going to happen.

A plan can have many components, the nitty gritty of financial aspects, but also things like - I want this psalm to be read or I don’t want anything from the bible to be read or this music playing. A plan can involve the room you will be in and different aspects that would make that feel safe and welcoming. An important part of laying out many of these practical things is that maybe you will not be able to share in the same way toward the end. Maybe you have heard people remark, “well, I don’t care what happens, I will be dead.” Nesbitt emphasizes how helpful this can be to your loved ones, to have a real idea of what you prefer. And if you generally don’t care, then it is still really helpful to write down things like passwords and other practical information that will be helpful to your loved ones.

Conscious dying is an art that we can choose to re-remember. With the help of a growing movement of death doulas and doulas in collaboration with hospice nurses, one can actively seek a sacred and holistic path toward exiting this world. May more of us contemplate the beauty of life to the point that we take care of ourselves and those around us through a shared understanding of our end-of-life journey.

For those that wish for some follow up from this article or to investigate these ideas further, Nesbitt points readers to the Threshold Care Circle and a book they put together called My Final Wishes. It can be found via their website: thresholdcarecircle.org

For those interested in connecting with a doula or just more information check out National End-of-Life Duola Alliance (nedalliance.org), Conscious Dying Institute (consciousdyinginstitute.com), and The Peaceful Presence Project (thepeacefulpresenceproject.org). Nesbitt is training through Anamcara Apprenticeship at the Sacred Art of Living Center in Bend, Oregon - apprentice.sacredartofliving.org

Luna Moth

Each day while walking on my south bound backpacking journey I experienced profound encounters with a variety of creatures, trees and other humans. I was usually awake by 5:30 am and on the trail by 6:30. Most of my interactions happened in the early hours of my day.

from Gifts of the Superior Hiking Trail by Mikkel Beckmen (Ramshackle Press 2023)

Illustration by Siri Marie Beckmen

Mikkel Beckmen did a solo thru hike of the Superior Hiking Trail in 2021. The 310 mile trail skirts Lake Superior, the largest freshwater lake in the world. On his 24 days of hiking he brought no music, electronics, or even books. Just a journal to record thoughts each day. The book has 24 chapters, one for each day of hiking the trail. It is an ode to self-discovery, the natural world, and one person's question, "Who am I in relation to wilderness and to the land?"

Each day while walking on my south bound backpacking journey I experienced profound encounters with a variety of creatures, trees and other humans. I was usually awake by 5:30 am and on the trail by 6:30. Most of my interactions happened in the early hours of my day.

I thought about these interactions as I walked. Each one revealed something - a gift or a secret about how to get by in my wilderness environment, and ultimately how to be in the world. My second day, way up in moose country, I came across a beautiful Luna Moth.

The Luna Moth is found in the northern parts of North America (Turtle Island).

The Luna Moth is rarely seen, even though it is one of the largest moths on earth. This is not because it is rare, but because the Luna Moth only lives seven days in their moth state. They have no digestive system and live briefly off the left-over energy they had as caterpillars. They are designed to move efficiently, and use energy sparingly.

I expended a lot of physical and mental energy each day; more than I was getting through the 10-15 pounds of food I carried in my pack. To make the whole journey, I realized I needed to be as efficient as possible. I needed to rely on stored energy and efficient movements over mountains, gorges and forests, and as I set up and broke down my encampments and prepared meals. I became adept at setting up my tent and cooking with the least amount of motion possible. Nine hours of sleep and being still on breaks helped as well.

It takes energy to move our butts from one place to the next. That we have chosen to burn dinosaur bones (fossil fuels) for the majority of our movement from one place to the next, has, in just over a century, brought us to the brink of extinction. I thought about the ways in which I might be more efficient in my energy use at home. How I move about, cook and use electricity.

The future is created by the choices we make in our everyday lives. The current situation is the sum of yesterday’s choices. The Luna Moth is designed to move with grace and efficiency for a reason.

How will you move today?

12,000 Years in the Driftless

The Driftless Region has had some form of human population for at least 12,000 years - since the retreat of the last glaciation, the Wisconsin. There is scant evidence for a previous population, but based on current findings elsewhere it is likely, and possible source material for another article. Archaeologists claim evidence of Paleo Indian (essentially their name for the oldest people’s discovered) dating back twelve millennium.The oldest evidence in the Upper Mississippi River Valley leads scientists to claim that bands (smaller groups of cooperating families) of hunters were moving two to three times per year and setting up small encampments. Spending summers on the rivers and winters deeper up into the many valleys, some over wintering in rock shelters throughout the area.

By Parker Forsell

from Issue #1 of Ocooch Mountain Echo

I am neither an archaeologist nor a historian, but trust that my aim is to help others understand the Driftless region now and in the past. It’s my sincere belief that you need to know where you come from to uncover who you are now. Feel free to write to me if you want to help improve or elaborate on unfolding the mystery of 12,000 years in this land.

The Driftless Region has had some form of human population for at least 12,000 years - since the retreat of the last glaciation, the Wisconsin. There is scant evidence for a previous population, but based on current findings elsewhere it is likely, and possible source material for another article. Archaeologists claim evidence of Paleo Indian (essentially their name for the oldest people’s discovered) dating back twelve millennium.The oldest evidence in the Upper Mississippi River Valley leads scientists to claim that bands (smaller groups of cooperating families) of hunters were moving two to three times per year and setting up small encampments. Spending summers on the rivers and winters deeper up into the many valleys, some over wintering in rock shelters throughout the area.

With all of our so-called sophistication, it is easy to become focused on the present and immediate future. We only represent a speck of time in the history of the region. European settlement occurred less than 200 years ago, and French trappers began first meeting First Nations people and mapping this territory 350 years ago. If the past 12,000 years of human history were a 12 inch ruler, “the United States declared independence less than a quarter inch ago, the automobile was invented a tenth of an inch ago, and the age of computers occupies the last one-thirtieth of an inch”, write Theler and Boszhardt in their indelible book Twelve Millenia. More than eleven and half inches of that one-foot ruler existed prior to European settlement.

Evidence and descriptions of early cultures is based on what archaeologists have been able to find; their descriptions are educated speculations on what people were doing and how they interacted with the land. As we move backward on the ruler, mostly in that first inch, archaeologists' summations have been informed by interactions with current First Nations peoples and their understanding of their ancestry and ways of living. Hard to believe, but archaeologists only started to systematically identify prehistoric remains in the early 1800s. Much of this was spurred by Europeans first encounters with effigy and conical mounds, and their mistaken theory that the mounds came from a mysterious Mound Culture that was separate from the ancestors of modern First Nations people. The intense interest around the supposed “Mound Culture” got the Smithsonian Institute involved in the 1880s, and Cyrus Thomas made the first series of extensive surveys and excavations in the Driftless area, which is still home to one of the highest concentrations of mounds in the country. Thomas worked on the study of the mounds for more than 10 years, culminating in the 700-page publication entitled Report on Mound Explorations of the Bureau of American Ethnology. The report concluded that the mounds were definitely constructed by ancestors of current First Nations people and that the idea of a separate Mound Culture was untrue.

If we wind the clock backward, we can imagine this area as it might have been at the end of the last Ice Age. More recent research points toward a warming and the beginning of a recession of the 1-2 mile high glaciers covering large parts of North America and Europe around 18,000 years ago. While the Driftless area was not covered by the glaciers, during the melting of the glaciers it is believed that ice dams formed in areas that surrounded the land mass. When these ice dams broke, tremendous, catastrophic amounts of water and debris poured into the Upper Mississippi River Valley and its many tributaries. Over hundreds of millions of years these valleys had eroded to the point where the elevations between river valley and bluff top were well over 1000 feet. When the deluge happened from the melting glaciers, so much water and debris poured into these valleys that the rivers covered the valleys from bluff top to bluff top. What we see thousands of years later are the scoured valleys, silted in to form massive sandbars. In fact, many of the Driftless’ well-known cities - Red Wing and Winona, MN, La Crosse and Prairie Du Chien, WI and Dubuque, IA are located on the glacial outwash from the massive melt-water floods pouring through the Mississippi River Valley.

It almost goes without saying that the intriguing, dendritic river valley landscape and uniquely carved mini-mountains, are what stick with travelers and inhabitants alike. There are literally hundreds of unique look-outs and rock faces throughout the 24,000 sq. miles of the Driftless ( an area larger than the states of Vermont and New Hampshire combined). According to history, people have been roaming these gorgeous hills for 120 centuries, meaning when the great deluge hurled through its many river valleys there were likely people, and animals, and artifacts swept up in the chaos, and small bands of extended community had to adapt post-flood.

Twelve thousand years ago bison, wooly mammoths, and mastodons would have been roaming the ancient valleys of the Driftless and late Paleo Indians were hunting with flute pointed spears. The rock source may have been from Silver Mound near Hixton, WI (an early mecca for stone tool making in the upper Midwest) or possibly from a handful of smaller rock source sites in the Driftless.

In 1897, four farm boys recovered almost an entire skeleton of a mastodon near Boaz, WI - it was prior to a flash flood in a headwater tributary stream of the Wisconsin River. When the boys were excavating the bones they came across a fluted point that was later identified by archaeologists to be made of Hixton silicified sandstone. Further investigations led the archaeologists to determine an area that may have been a megafauna kill site (an area hunters drove animals toward for harvesting purposes). The articulated skeleton of this mastodon can still be viewed today in the geology museum on the University of Wisconsin - Madison campus.

By ten thousand years ago, the Pleistocene megafauna were gone and the environment was rapidly changing toward the warm phase known as the Holocene era, which still continues today. Archaeologists refer to the period after Paleoindian as the “Archaic”, and it covers a span of time from 7,000 B.C. to 500 B.C. At the beginning of this period peoples were adjusting to increasingly warm and dry conditions, which began the march of prairie and oak savanna vegetation throughout large portions of the Driftless. Archaeologists also presume that water levels of the rivers would have been down during this phase and encampments would have been built lower in the river valley, leading to submergence of historical evidence when water levels began to rise.

During the late Archaic period archaeologists mark a change in the stone points, reflected in spear points that were detachable, so a hunter could maintain their spear and attach a new point. Ground stone tools for woodworking, such as stone axes begin to be more prominent during this period. A well-known Late Archaic site is the Durst Rockshelter in Sauk County, where unusually a human burial was found. These rock shelters were used for thousands of years, most likely during the cool-season months, but normally individuals that died during the winter would have been buried during the summer months during larger macroband gatherings. One of the interesting aspects of the Durst Rockshelter is the recovery of artifacts from many different periods of time over thousands of years of habitation.

Another interesting Late Archaic pattern relates to artifacts found in association with what has been termed Red Ocher Culture. The red ocher refers to human burials and artifacts covered with a bright red iron oxide powder composed of hematite. Artifacts most common in these burials are copper bracelets and beaded jewelry and large flint knives. Some well-known Red Ocher sites are along the Turkey River in northeast Iowa, particularly Turkey River Mounds, where 17 inch blades have been found consisting of Burlington chert, likely sourced near St. Louis, MO. These are actually extremely rare finds in the Driftless, but point toward a flowering of extensive trade networks and what archaeologists believe may have been connected to exchanges between macrobands, related to easing possible tensions related to territory. One other observation is that these burials containing copper artifacts and ceremonial flint knives have mostly been found in burials containing women and children, including infants.

The period archaeologists refer to as Woodland covers the time period from 500 B.C. to 1150 A.D. The main turning point here is the evidence of pottery. Elaborate pottery has been found dated to the Late Woodland cultures at Effigy Mounds National Monument in NE Iowa. The pots were made without a pottery wheel, and it remains unknown as to how the pots were fired, no kilns have been found so it assumes the pottery was stacked and fired in a manner without a kiln. The fragility of pottery is also believed to have contributed to a shift toward a more place-based lifestyle among the people, rather than to two-to-three movements per year of the macrobands.

During the Woodland period is also when the evidence for mound and effigy mound building proliferates the full length of the Upper Mississippi Valley of the Driftless region and its many tributaries. There may once have been at least 10,000 mounds between Dubuque, Iowa, and Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin. Unfortunately, at least 90 percent of these sacred site burial mounds have been destroyed by agriculture and development. Preservation is growing though around the remaining sites, and we are fortunate to have both scholars and informed citizens working to conserve and educate others about these unique and special places throughout the region.

Over the years, several valuable archaeological studies by numerous University of Wisconsin programs and the Milwaukee Public Museum have helped to elaborate the story of the peoples living from the Woodland onward into the Oneota period. Many investigations have centered around the village of Trempealeau, WI and its immediate environs. Evidence of both the Hopewell culture and expatriate Cahokian (Mississippians) originating in central IL - St. Louis, MO area has provided much intriguing information related to the lifestyles, burial practices, and star-based cosmology influences of these groups.

During the Late Woodland period beginning in 600 A.D. is when archaeologists observe what they believe to be the beginnings of the tribes. In addition to wide use of pottery, it is important to note the point at which a northern adapted 12-row flint corn is first observed (around 1000 A.D.). A long journey from its transition from native teosinte grass more than 4000 years before in Mexico.

The Oneota Culture phase marks the time period people were occupying the Driftless region from 1200 A.D. to 1700 A.D.; it is at the very late stages of this period that French explorers first travel through the region and begin writing about their initial interactions with the Native people of the area. What follows is a troubled part of our heritage for those of us who trace our descent to European people. Our ancestors tricked, stole, and massacred in an effort to take the land from First Nations people who had been living here for thousands of years. It is a personal aim of the author to continue to write and seek out others who can tell these stories.

There is still much history of the Driftless to tell of these last 300 years - the last ¼ inch or so of the ruler. Not all of it is bad, and much of it can help us discover who we are as citizens of a bioregion. We can’t go back, but we can strive to better understand our history, geography and the cultures who make this place home. It is one of the most amazing stretches of land on the continent with a history and a heart and soul to still be discovered by all of us. A bioregion is a kind of “spirit place” that only deepens in meaning when we are able to combine both cultural and natural history. The longer one lives in an area or “lives into” an area the more it may actually grow into a force within you.

Note: the entire breadth of this article has been based on the book Twelve Millenium (Archaeology of the Upper Mississippi River Valley) by James Theler and Robert Boszhardt, 2003, University of Iowa Press. It is an amazing book that may get too detailed at times for many readers, but nothing like it exists in terms of Driftless history.

Two other publications that readers might also enjoy are:

Roadside Geology of Wisconsin by Robert Dott, JR. and John Attig, 2004, Mountain Press Publishing - I believe they have these for most States, but this one is really good.

Oneota Flow (The Upper Iowa River & Its People) by David Faldet, 2009, University of Iowa Press.

Oak Center General Store

Walking through the front door of The Oak Center General Store is like stepping back in time. As you push the heavy, wood door open a bell rings, and your first steps are onto a creaky, wooden floor. A long mercantile counter runs the length of the room on one side, and the other side has an old wooden ice box filled with local sodas and assorted items that need to be kept cold.

A Place for Community Since 1913

By Bill Stoneberg

from Issue #2 of Ocooch Mountain Echo

Walking through the front door of The Oak Center General Store is like stepping back in time. As you push the heavy, wood door open a bell rings, and your first steps are onto a creaky, wooden floor. A long mercantile counter runs the length of the room on one side, and the other side has an old wooden ice box filled with local sodas and assorted items that need to be kept cold. Throughout the storefront there are a small amount of produce and food items along with various goods one might expect to see in a store that caters to free spirits. Entering the place is a kind of time-travel, inducing what I can only describe as a feeling of magic.

I first became aware of The Oak Center General Store in early 2020. My partner and I were excited that Erik Koskinen was scheduled to play. We noticed it was near Lake City, MN and when we clicked on the link to the venue and saw pictures of the old general store, we felt we had to go. Then COVID-19 hit. The Erik Koskinen show was cancelled along with many others. We were very disappointed. The photos of the interior of the venue were so intriguing, it just looked so beautiful and like something from another time. We decided, show or no show, we must go see this place. So, one Saturday afternoon we headed to The Oak Center General Store.

As we entered the store, we were greeted by two dogs. Then, as we began to browse the store, a slight, slow-moving figure appeared in the back doorway. “Hello there!” said Steven Schwen, proprietor, and resident of The Oak Center General Store. We greeted Steven and informed him that even though the show was cancelled, the photos of the venue were so incredible, we just had to see the place for ourselves.

Steven gave us a tour, imparting many little details about the history of the building from both before and after he acquired it in 1976. On this day, and through subsequent visits, I have learned that no time with Steven does not also involve a generous mixing of some stories of his involvement in fights for social justice and the hippie movement of the 1960s and ‘70s.

Oak Center is an unincorporated community that once had a post office, a creamery, and various other businesses, including the general store. The store first opened in 1913 and operated as a general store, implement dealer and community center until it closed its doors in 1970. Steven Schwen resurrected the store in 1976. Since that time Steven has operated the store and a small farm called Earthen Path Organic Farms; growing fruit, herbs, and vegetables to sell in the store, to a local CSA (community supported agriculture) program and for local farmer’s markets. Oak Center General Store is at the front of the building, with an adjacent woodshop, and upstairs is the beautiful concert or meeting room with a built-in stage.

The following is from an interview I did with Steven in December of 2021:

Can you tell us a little about the history of The Oak Center General Store?

I haven’t been here the whole time, it's 109 years old! It was built in 1913 by Sophie Siewert and A.J. Siewert. Sophie's family had the money, and AJ was the wheeler dealer. The stories just kept walking in the door from the day I got this place.

When did you acquire the store?

1976. The 200th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence! It was my declaration of independence!

I was going to ask that! But this was always a general store like it is now, right?

Well it was more a general store than it is now and it had been closed for six years when I found it.

So, it operated from 1913 until 1970 as a store?

They bought and sold wool, they trucked grain. They sold Case equipment and moonshine…

All the important things, right? So, this was a real important center for the area?

It was. It was a community center.

What is the history of your involvement here at the store? What was your vision? What were you doing with it when you first acquired the property?

I was doing woodworking and cabinet making and remodeling on the side to pay the bills. I started cabinet making because I didn’t have enough income coming in from making furniture for people. I was trying to be affordable for my neighbors and none of them could afford to pay a decent wage to a hippy type who was making furniture. But a lot of the local neighbors were really supportive and allowed me to make some really creative stuff.

In fact, this table here with these carved lion claw feet. I made this for a neighbor that showed me one in a Kmart catalog. The Kmart table didn’t have carved feet, it had just a profile band sawed out and it was particle board with oak veneer on it. He said it was four hundred bucks. He then showed me a table in a furniture magazine that was twelve hundred bucks and had real solid oak and carved feet. He said we like the price on this Kmart one, but we like this other one better. I said, “You know what, there’s a lot of difference between those two tables, but I’ll do the best I can.” So, I made the table, and I figured my wage at two dollars an hour and it came out to six hundred bucks.

So I told him, “Well, the cheapest I can sell this table is six hundred bucks, and if you can’t pay that then I’m going to keep it.” I’m glad I did because there have been a lot of very, very good fellowship times around this table when we have a concert. People come and gather round this table cooking food up for the concert. We actually had a potluck dinner around this table with Eugene McCarthy. And the room was full of people. I have a picture; I can get it if you want to show it on your radio show.

------

We both chuckle a bit about showing photos on the radio, but the story of the table brings us to the reason I stumbled upon the Oak Center General Store to begin with, music. You see, part of every musical performance that happens here is the sharing of a farm fresh meal. Shows at the General Store are more than just a music performance, they are about sharing art, ideas, and community. Musicians seem to love playing the store as well. Trempealeau, WI singer-songwriter John Smith said, “It’s like playing inside a guitar.” The list of artists that have performed here over the years is full of recognizable names, including Mark Olson from The Jayhawks, Greg Brown, Charlie Parr, David Huckfelt and also his former band The Pines, Humbird, Erik Koskinen, Chris Koza, The Federales, Molly Maher, Pistol Whippin’ Party Penguins, Dean Magraw, and Bill Staines who had played here every year for over 40 years right up until his death this past year.

Trempealeau, WI singer-songwriter John Smith said, “It’s like playing inside a guitar.”

------

How did you start hosting musical performances?

My vision when I first moved here was influenced by a commune that was called the Orinoco G Church. I moved there in ‘72 when I graduated from college, after having gone through the whole anti-war protests and the Chicago Eight Trials and Crosby Stills and Nash singing about “your brothers bound and gagged” you know. That was all happening right while I was going to school.

and you moved to a commune here in Minnesota…?

Yea, you know, building a whole new world. We were pretty ambitious. Building from the roots up. Starting with the land, we stopped using chemicals and formed co-ops, building a new economy.

It sounds like the experiences in the commune and the time period carried through here at the store and with the farm.

Oh yeah, like I said, I was permanently affected.

So, you got this in 1976, what did you do with it right away? Start the farm?

Well at that time I was calling myself a missionary farmer. I was trying to become the advanced guard of the organic back to the land movement here in my home state of Minnesota. My neighbors were a little wary, or skeptical when some guy with long hair and a beard moved in. Some families around here wouldn’t let their kids even come in store!

So, you got the store and you’re doing missionary agriculture work. How did that lead into the music?

When I first got this place the stories from old timers came in through the doors. I heard a whole lot of the history of everything that happened here. Including the bootlegging story about the Seiwerts and people telling their kids they couldn’t come in here because I was a communist! This friend of ours, David, was coming by and I mentioned how we used to have this really great little get together back in Oronoco when I lived in the commune, and we would show movies. David said, “You can check movies out from the Rochester library, let’s do that again.” So, after doing those movies for a little while, David said, “Let’s do a square dance.” So, we hosted a bunch of musicians from the Winona area who called themselves the Sugar Hill String Band.

The Sugar Hill String Band came up and we had Bob Bovee and Gail Heil calling the first square dance. You know Gail died a few years ago, they always used to come together. Pop Wagner used to come and call once in a while. The square dances filled the place up with back-to-the-land homesteader types. You know the old hippy types who had gotten back to the land? They came out of the hills! It was great times. I think we had maybe more than a hundred people for a square dance. We had five-gallon buckets with boards on them and old rocking chairs and kitchen chairs to seat everybody. So pretty much everybody had to be standing up or dancing. I’m trying to remember how many squares we had going up there. We probably had at least two squares going and maybe it was three.

Actually, that wasn’t the first music. The first music was the first year. The power company and the phone company were threatening to shut us off. The only income we had, the store, wasn’t much income really, and my woodworking hadn’t reached a level where I was able to make enough to cover the payments and the bills. So, utilities were threatening to cut us off, and a friend of ours that came by to fix one of our refrigeration units said, “Well, you know what? I’ve got a band and we’re short on gigs. You guys are short on money. Why don’t we have a dance here and we’ll split the gate. You supply the place, and we’ll supply the music and the beer.” And they did supply the beer. It was kegs of beer and plastic cups.

The band was called Wild Oats and the first people that walked in were all bikers in leather and one of them said, “Wow look at this place there’s nothing you can wreck!” Actually, we anticipated this might happen so I had sheets of plywood screwed to the fronts of all of these shelves to protect our stereo and our dishes and everything else from damage and he pounds on the front of the plywood and says “Look there’s nothing you can wreck!” I’m thinking, aw jeez this is not going to go well. So, they got upstairs and the band’s playing and it's one in the morning and they run out of beer. There are overturned plastic cups laying all over the floor and beer is two inches deep in the middle of the floor. These floor joists are 34 feet long you know so there’s a slight sag to the middle of the floor and the spilled beers all kind of ran to the middle and it's two inches deep. And these guys, who showed up in Harley boots and leather leggings and stuff, are taking their shirts off and running and sliding in the beer. So it’s splashing up on either side like the wake from a water skier you know. Just the spray. So eventually they’re getting up on stage taking up a collection to get more beer. My first wife Nan and I, we were sleeping up there and we had mattresses out on the floor. I got up on stage and said “You know what? This is our home, this is our bedroom, we have to sleep on this floor! No, that’s it, we’re done. Everybody go home!”

They all complained, and everybody started to leave. We carried up wood shavings from the shop and dumped wood shavings and sawdust all over the floor to soak up the beer. We shoveled the sawdust up and carried it out to the barnyard. We got it all cleaned up and we went downstairs and here’s a neighbor kid who was still in high school, passed out. He had puked on the couch upstairs already, he’s passed out in a snowbank outside, and can’t find his keys! He just lives a mile down the road you know. We turned to go back up the stairs and there’s a couple making out on the stairs and by this time it’s four in the morning. We looked at each other and said, “Folk music.” (laughs)

She (Nan) was really into Bill Stains, who just died two days ago by the way (December 5, 2021). Probably one of the longest running troubadours in the U.S. He was really well known; you’ve probably heard some of his stuff before.

So folk music…

Well, we decide we’re doing folk music and the first one she wanted to have is Bill Staines. But this friend of ours who got us steered towards doing music, David, he brought us an album of Greg Brown. We liked it, so David somehow got in touch with Greg Brown. I believe this was 1978.

So, it all got going pretty quickly then?

Yea, yeah. That first show we split the gate with this band and got all the beer and sawdust cleaned up and it paid those first two bills. We decided we were going to do folk music. So, we go up to the Coffeehouse Extemp above the New Riverside Café in Minneapolis where Bill Staines was playing. Bill ended up being the longest standing regular musician that we had here. He played here every year for forty years. I think we had to cancel once because of a snowstorm. Bill used to show up with his cowboy boots and his cowboy hat and he was an incredibly versatile vocalist. He was spot on with his, what’s that word for being able to sing right on the…

pitch?

Perfect pitch! He had perfect pitch. He had this song about 18 wheelers where the line was “I grew up with my face in a roadmap.” Nan and I had three kids, and the youngest was Jesse. He’s still the youngest. The kids always thought that he was singing “I threw up with my face in a road map.” So, one of those times when he (Bill) was playing here Jesse got his cowboy hat and his cowboy boots on. Bill’s doing the soundcheck and he’s up on stage tapping his foot and playing his guitar singing that 18 wheeler song and Jesse’s right next to Bill trying to tap his foot in sync with Bills foot and he’s singing “I threw up with my face in the roadmap”! (chuckles) You know, life has been magical here. The Folk Forum concerts really have brought a lot of magic through the doors.

Actually, we called it Folk Forum not because we were going to do folk music. I was working with some people out of Millville that were doing the North Country Anvil, it was a regional magazine that quit printing probably 20 or 30 years ago. There was a community of people that had developed around the North Country Anvil and the stuff that was happening with the Folk Forum. We had been talking about the folk schools like in Kentucky and down in The Carolinas, so we called it Folk Forum. The intention was that the Folk Forum was going to be a forum to kind of try and enlighten people about treating the soil right and alternative economies, and about opposing nuclear weapons and warfare.

Different ways to do things.

Yea, yea. I don’t want to sound egotistical but to raise the level of consciousness a notch or two, you know? And the first forums that we did weren’t music, except for the two square dances and those first two folk musicians. We did workshops on renewable energy, how to build your own solar collectors, how to build your own wind charger, grafting, organic farming, horse farming, and holistic medicine actually!

When I quit med school, I went out to Pennsylvania to go to a homeopath school and get certified as a homeopath. I asked the person that was instructing at the school if he would come and do a workshop on homeopathy at Oak Center as part of our holistic medicine series and he was actually a well known banjo player and pedal steel guitar player! In New York City at one time they called him “the wiz kid of banjo.”

So, did he play here too?

He did a homeopathic workshop on Friday night and a pedal steel banjo concert the next night.

So, you’ve been doing the Folk Forum for almost 45 years?

You know we had something scheduled with Bill Staines on the last Sunday in February, which he had done consecutively every year for more than 40 years.

So he was going to play in February 2022?

Yep. And I was thinking when he called, gosh, I hope you can get up to the stage. He’s 74 and I’m only 71 and I have trouble getting up on the stage. Bill Staines was a true troubadour. He just told stories from one end of the country to another.

You said you had communicated with Erik Koskinen and David Huckfelt recently about playing here again.

David’s a really great guy, and when he played with Benson Ramsey in the Pines, they would sell out weeks ahead of time. His dad Bo Ramsey used to come here with Greg Brown, and they would always sell out. And then Bo Ramsey married Greg Brown’s daughter.

But David and Benson used to be a show that people came to. But as far as concerts coming up in the future, I was talking with Erik. He was back in New York state with his mom. Erik said why don’t we see how things look in January. Let’s get in touch in January. I’m waiting to schedule something with Erik.

Charlie Parr has said that he wants to come back too, and you know he always sells out. But that’s one thing we’ve been holding out on with Charlie, he always packs the house. I don’t know if we can pack this place and have people feel comfortable.

------

Steven’s words, “I don’t know if we can pack this place and have people feel comfortable” echoed in my head as I left the store. Like I said, if I were to describe my first time walking into The Oak Center General Store in two words, “It’s magic.” My experience at The Oak Center General Store has been both wonderful and disheartening. Wonderful because it takes you back in time. It is a window into another world where the unchanging past collides with a possibility filled future. And for the musicians that play here, well, like singer-songwriter Johnsmith said, “It’s like playing inside a guitar.” It is also disheartening because of the times were in, times that would solicit a comment like, “how do you pack the place and still feel comfortable?”

These days The Oak Center General Store often sits empty except for the echoes and shadows of the life that has passed through it over the past century. This place needs that life. It needs to be packed; packed with people sharing experiences of art, music, food, and most of all community. What The Oak Center General Store really needs is community. Community is what we all need right now. Perhaps if we channel life into places like The Oak Center General Store, they will channel life back into us.

Learn more about The Oak Center General Store at www.oakcentergeneralstore.com

The Root River: Gah-hay Wat-pah

Meanings about places emerge through the stories we tell. These stories may involve memorable experiences, iconic landmarks, or points of personal inspiration and awe. Over time, places and their stories change. Names change. Even at the foundational scale of geology, change is constant. The porous karst region of far southeastern Minnesota – with its 13,000 years of human history and precipitous bluffs of limestone, sandstone, clay and dolomite – offers one connecting thread: The Root River.

by James Travis Spartz

Gah-hay Wat-pah, Where the Crows Nest

By James Travis Spartz

from Issue #3 of Ocooch Mountain Echo

Meanings about places emerge through the stories we tell. These stories may involve memorable experiences, iconic landmarks, or points of personal inspiration and awe. Over time, places and their stories change. Names change. Even at the foundational scale of geology, change is constant. The porous karst region of far southeastern Minnesota – with its 13,000 years of human history and precipitous bluffs of limestone, sandstone, clay and dolomite – offers one connecting thread: The Root River.

The Root is fed by surface water run-off and countless snow-cold springs. Labyrinths of water-carved rock creep deep underground, fertile alluvial terraces carry multiple histories, and remnant niche species — Laurentide remainders (i.e., Refugia) — like the Iowa Pleistocene snail and Northern Monkshood sequester on algific talus slopes. Plants, animals, rock, and fungi — human and more-than-human communities — share the greater Root River watershed across six counties and 1,670 square miles of driftless riverine terrain.

Like all places, the river valley is a pluriverse. It is traditional hunting grounds for Eastern Dakota, Ho-Chunk, Sauk & Meskwaki (Fox), and Baxoje (pronounced Bah-Kho-je) or Ioway peoples; refuge and retreat for leaders such as Dakota chief Wapasha I (who chose it as his dying ground in 1805–06) and, later, Ho-Chunk chief Winneshiek (aka Coming Thunder), who had a favored camp between present-day Houston and Rushford; the public lands of Richard J. Dorer Memorial Hardwood State Forest; cultivated land with fencerow-to-fencerow corn and soybeans; and sites of tallgrass prairie and oak savanna restoration, organic agriculture, concentrated animal feeding operations, and grass-fed livestock. Trout streams simultaneously host rich biodiversity and are threatened by overloads of bacteria, nitrates, and sediment. Places, and place names, are singular and plural. Histories and meanings – the stories we tell – capture our attention in different ways, at different times, for innumerable reasons.

The Root River has gone by many names in Dakota, Ho-Chunk, French, and English. Historian Franklyn Curtiss-Wedge wrote in 1912 that the blufflands of southeastern Minnesota “generally… remained in the possession of the Sioux from some time before the days of the early explorers until the proclamation of their treaty of Mendota, February 24, 1853.” In practical terms, Curtiss-Wedge writes, the traditional hunting grounds of the Root River valley were “under the domain of Wabasha’s band” of Mdewakanton Dakota, but were also visited (and contested) by Ojibwe hunters from the north, Ho-Chunk peoples from the east, and “by the Sacs and Foxes who lived to the southward, and by the Iowas who lived to the westward.”

The Root has gone by its current name since about 1806; since then “the Root river has been a feature of every map of Minnesota,” writes Curtiss-Wedge. The waterway first appeared on a non-Indigenous map in 1703, as “R. des Kicapous,” and Curtiss-Wedge details various mapped French-Canadian (and other) names given for the Root River: Quicapon, Quikapous, Quicabou, Quicapoux, Macaret, Quicapous, Yallow, Quicapoo, Yellow, and Carneille.

The most common etymology today connects “root” with the town and township name of Hokah. “The name of the town, and the village which is located at the first eligible point up the stream” is an Indigenous-derived name for the river and town site, writes the Rev. Edward D. Neill in his 1883 History of Houston County. Hokah sits upon a high terrace and ancient village site. Alluvial terraces are common through the river valley, higher than the flood plain but well below the 300- to nearly 600-foot-high bluffs. Neill notes that the village and the river are also “said to have been… the name of a powerful Indian Chief whose village, before the disturbing elements of civilization appeared, was on the beautiful spot where now stands the village of Hokah.”

The City of Hokah has echoed Neill in stating “the site of Hokah was, at its founding, an Indian village. The name of Hokah is derived from their leader, Chief Wecheschatope Hokah. The English translation is Garfish.” No references are given, but the language is very similar to names found in Caleb Atwater’s recollections of travels through the old Northwest. Atwater’s first-hand account includes details of an 1829 treaty council at Prairie du Chien with leaders from “the Winnebagoes, the Chippeways, Ottowas, Pottawatimies, Sioux, Sauks, Foxes, and Munominnees [sic].” In constructing a rudimentary “Grammar of the Sioux Language,” Atwater includes “Wecheschatope” as the listing for “Chief” and “Hokah” as meaning “garrfish.”

In 1883, Lafayette Bunnell wrote in his History of Winona County that the Root River was known to local Ho-Chunk people “as Cah-he-o-mon-ah, or Crow river, and not the Cah-he-rah, or Menominee river, as stated by some writers.” Bunnell writes that local Dakota peoples with whom he was familiar (which included the coterie of Joseph Wabasha, or Wabasha III) also called the Root River “Gah-hay Wat-pah, because of the nesting of crows in the large trees of its bottom lands.”

Henning Garvin, a linguist with the Ho-Chunk Nation, explains that "Kaaǧi is the Hoocąk word for Raven, though it is often used for Crow as well. It is also the name we use for the Menominee people,” says Garvin, which probably led to the misinterpretation Bunnell mentions. In an email exchange with Mr. Garvin (who collaborates on Ho-Chunk (Hoocąk) language revitalization efforts within the Nation), he suggests Bunnell’s phonetic spelling of “cah-he-o-mon-ah” as likely meaning “Kaaǧi Homąra,” or Crow/Raven nesting place, as Homą means nest in Hoocąk.

As Westerman & White note in Mni Sota Makoce, Indigenous place names record sense-of-place relationships in many ways — often by giving “descriptive names to special features of the landscape.” It is through such place names, stories, and experiences “that we understand the power of place” as plural rather than singular — sacred, pragmatic, historical, and contemporary — a multiplicity of meanings across a range of worldviews.

The Root River meets the Mississippi just below La Crescent, Minnesota, and across from La Crosse, Wisconsin, to the east. Prior to straightening and adding levees to the lower Root in 1917-18 — construction of “Judicial Ditch №1” — the mouth of the river was reedy, with minimal flow; a marshy area adjacent to Broken Arrow slough and Target Lake.

In a footnote to his 1895 re-publication of Zebulon Pike’s 1805 (and ’06 and ’07) exploration of the Upper Mississippi River, Elliot Coues notes: “The slough on the Minnesota side above Root r. is called Broken Arrow — and this, by the way, is connected with a certain small Target lake.” There is “no doubt,” Coues writes, that “some actual incident gave rise to both these names.”

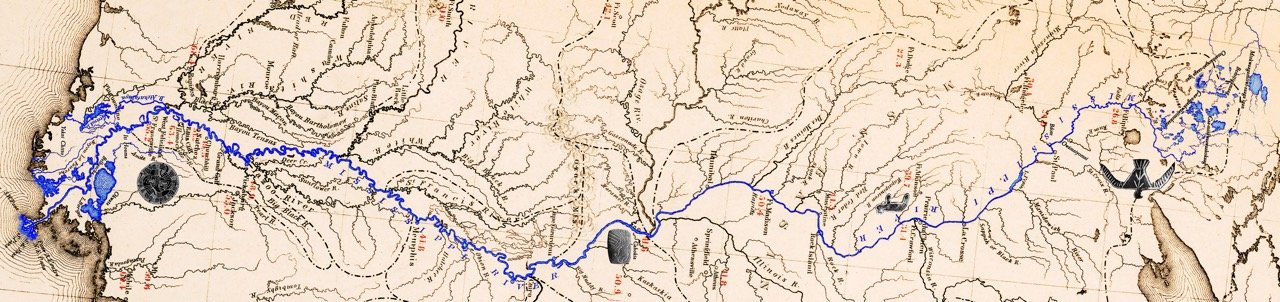

Map_of_the_Country_Embracing_the_Route_of_the_Expedition_of_1823_Commanded_by_Major_S.H._Long — Public Domain

Keating’s 1824 account of Major Stephen H. Long’s “expedition to the source of St. Peter’s River” includes a reference to crossing the “Hoka (Root)” river in 1823 when the strawberries with their “fine fragrance” were “in a state of perfect maturity.” The riverine trenches or “sinks” within five to six miles of the Mississippi’s western shore prompted “greater difficulties than had been anticipated” across “extremely rough and hilly” terrain as Long’s expedition moved north through Driftless Iowa after crossing the Mississippi from Ft. Crawford at Prairie du Chien.

A Dakota guide, Tommo or Tammo, led Major Long’s party across prairie ridges and through transverse valleys to maintain access to fresh water. The forested slopes, Keating writes, “consisted principally of oak, basswood, ash, elm, white walnut, sugar tree, maple, birch” and aspen. A “thick undergrowth” of hazel and hickory were seen in the woods while, “wild rice, horsetail,” and “may-apple” were found in the bottoms. Wild rose charmed the eye and strawberries satisfied the palate, Keating writes, while a “large herd of Elk were seen… by the boys of the party… in search of the horses that had strayed during the night.”

Tommo, or “Tammo, Tamia or Tah-may-yay,” writes Lafayette Bunnell in 1897, “was a good guide, and from the description given of the route taken by Major Long from Prairie du Chien, it is clear that the most direct trail was taken where water could be had.” The party appears to have followed an ancient trail through what is now central Houston County. “From the crossing of Root river,” Bunnell writes, “the party came up Money Creek and down Pleasant, or Burns valley, to Winona.” South of the Root River, in Spring Grove township, settlers named Indian Trail Road (where present-day Houston County Highway 8 meets Highway 44). Moving north out of Houston, this trail follows the same trajectory as present-day Highway 76, up Money Creek valley and across the ridge at Witoka, before winding through Pleasant Valley (Winona County Road 17) towards the Mississippi, which flows west-to-east at Winona.

Writing in 1920, Warren Upham summarizes the varied names given the Root River as:

…called Racine river by Pike, Root river by Long in 1817, and both its Sioux name, Hokah, and the English translation, Root, are used in Keating’s Narrative of Long’s expedition in 1823. With more strictly accurate spelling and pronunciation, the Sioux or Dakota word is Hutkan, meaning Racine in the French language and Root in English, while the Sioux word Hokah means a heron. Racine township and railway village in Mower county, and Hokah, similarly the name of township and village in Houston county, were derived from the river.

Hutkan is the spelling used by Riggs (1852) and Williamson (1902) in their Dakota-English dictionaries, Upham writes, “but it is spelled Hokah on the map by Nicollet, published in 1843, and on the map of Minnesota Territory in 1850.” In the entry about the town of Hokah, Upham also declares it “the site of the village of a Dakota chief named Hokah,” though provides no direct reference — a common shortcoming of Upham’s tome Minnesota Place Names.

Paul Durand both echoes and clarifies previous place name claims in his book Where the Waters Gather and the Rivers Meet. “It was not until Keating’s narrative of Long’s expedition in 1823 where similar Dakota words HO-KA and HU-TA were confounded,” Durand writes, adding that “Hoka is heron and has no place here” (p. 28). He also repeats Bunnell by stating “this river was known as CAH-HE-O-MON-AH or Crow River by the Winnebago.”

Place names, like other pointing-and-naming, help us understand, categorize, remember and connect past to present and future. Place names have also been used to obscure and erase Indigenous ways-of-knowing, reconfiguring how, where, and why settlers encroached west in pursuit of a supposed Manifest Destiny.

The stories of Minnesota — of Mni Sota Makoce — write Westerman & White, include “oral histories and oral traditions” and “are reflected in the place names of this region where Dakota people have lived for millennia and where they still maintain powerful connections to the land.”

Settler stories in small towns throughout Minnesota often (and conveniently) forget about deeper pasts, fostering a disconnection from land and land-use while facilitating its degradation, often leaving tainted soils and waters for future generations. Creating deeper connections to the lands and waters we Midwesterners call home — across eras, cultures, languages, geographies, and ecologies — helps all who live in these special places acknowledge and appreciate the changes of our past, challenges of our present, and opportunities for the future.

Header photo: Root River at Rushford (G.G. Grossfield, undated). Courtesy of MN Historical Society.

Tribal Resources:

The Ho-Chunk Nation: https://ho-chunknation.com/

Baxoje | Iowa Tribe of Oklahoma: https://www.bahkhoje.com/

Meskwaki Nation | Sac & Fox Tribe of the Mississippi in Iowa: https://www.meskwaki.org/

Prairie Island Indian Community: https://prairieisland.org/

Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community: https://shakopeedakota.org/

James Travis Spartz was born and raised in Driftless Minnesota. He is an essayist and performing songwriter based in Madison, WI. He is currently a writer for UW-Madison's Institute for Research on Poverty and a faculty affiliate with the Nelson Institute's Center for Culture, History, and Environment.

Cabin Concerts

Gary’s tranquil property, surrounded on both sides by the river, had long been adored by family and friends alike.

Bring a Slice of Americana to the Turkey River

By Brian Gibbs

from Issue #1 of Ocooch Mountain Echo

It all started in the summer of 2020, with a half a dozen doughnuts and folk legend Charlie Parr. We were about four months into the COVID-19 pandemic and I spent those months watching all the music festivals I planned to attend that summer slowly get cancelled. Desperately craving both live music and gathering with my community, I reached out to my friend Gary and suggested we line up some live music at his cabin.

Gary’s tranquil property, surrounded on both sides by the river, had long been adored by family and friends alike. Charlie’s gig was a trial run for hosting live music at the cabin. It was a bare bones set up with only natural lighting, no amplification and a few dozen people in lawn chairs but the evening was magical. The only thing sweeter than the pastries was the sound of Charlie picking on his resonator guitar and his voice quivering among the river bluffs.

On a long cold January night several months later, the vision of creating an outdoor summer cabin concert series of americana/folk music was created over some craft beers with Gary. The reasoning was threefold: to create a safe space for musicians to share their music during a pandemic, to build community in a rural region of Iowa and to give us something to look forward to during an uncertain time.

Having never booked more than a single act, the thought of booking a whole summer was a bit daunting. However, after confirming the first few bands, I quickly found myself inspired and had a lineup of 10 concerts booked, including a two-day Campout at the Cabin weekend. All of the planning for the concerts was grassroots; I launched a private Facebook group to announce the shows, worked closely with my wife to develop a lineup poster, t-shirts and stickers, and recruited friends to make homemade food and drinks for the bands. However, the biggest piece of the puzzle was how to safely get dozens of people down to the remote cabin.

Getting There

There’s no physical address to the cabin; only a white sign that says No Trespassing Level C Road Limited Maintenance. If it wasn’t for an old, galvanized steel corn wagon outfitted with a tarp canopy, padded boat cushion seats and a sign that says “Cabin Concert Shuttle,” visitors may have never known they arrived at their destination.

A hilly ridgetop gravel road above the Turkey River takes visitors through a mature forest. Visitors arriving for the first time may have been alarmed at the sight of the sign that says “Bridge Out” as the tractor wagon tips over the first steep hill. At the bottom of this hill, the forest opens up into a large tallgrass prairie, with a patch of white pine trees in the middle. Looking ahead folks can see the 200 foot tree-lined limestone bluffs of the Turkey River. One more steep drop and a large weeping willow tree signals the beginning of the grass parking lot and the end of cell phone service.

A scattering of balsam fir, tamarack and white pine trees provides a Northwoods backdrop for Gary’s off grid cabin that he built with the help of a few family members. A large, roofed porch held together with a few gnarly red cedar posts makes an excellent hangout spot. The cabin features a wood stove, catwalk and sleeping accommodations for up to seven. Outside, a rustic outhouse contains a smattering of whimsical signs inside that have been gathered from across the country. A neon green “pottytime, excellent” sign also provides guidance to a more sophisticated lighted porta potty.

Just past the cabin is a large grassy area that Gary transformed into the main concert grounds. He converted a cedar structure that was originally constructed to be what Gary called his “hammock shack” into a stage to host the bands. It slowly evolved over the summer to include a hodgepodge collection of nature signs and river memorabilia. The stage faces the river and the limestone bluff on its opposite bank serves as a natural amphitheater. A walk down the grassy knoll puts visitors on a sandbar where a gentle riffle wraps around the beach and creates a tranquil ambiance heard during the acoustic shows. As part of the concert décor before each show, Gary rows a rowboat to the middle of the river, anchors it and sets up a spotlight to reflect off a towering white pine tree. Numerous trees are also wrapped with lights and some of them have tiny dots reflecting in their canopies. Gary says the setup was inspired by attending shows at the late-night stage of the Blue Ox Music Festival.

Cabin concert goers have the option of primitive camping along the river or can opt for a more remote experience further in the woods. Folks that stick around through the night are often greeted with some campfire jams and sing-a-longs as well as some spectacular star gazing. In the mornings, community breakfast is cooked over the fire and stories of the show are shared over steaming mugs of coffee.

The Shows

By the time Memorial Day weekend rolled around I was nervous as a cat to host Minneapolis band Good Morning Bedlam as the first act. A late afternoon text from them saying they broke down on the side of the road by Rochester did nothing to quell my anxiety. Thankfully, the band was able to get their van fixed and the folks down at the cabin just spent a little more time soaking in the scenery as they waited for the trio of musicians to arrive. Within ten minutes of arriving at the cabin, the band was down on the stage and entertained the crowd all night long with their furious folk tunes.

The ante was upped for the second show with well-known Iowa musician William Elliot Whitmore in town. Will has been a longtime favorite of my music community. I’d seen him perform at several venues over the past decade and was thrilled to have him perform at the cabin. With his first steps on the cabin porch, Will said he felt right at home and was excited to play his first live in-person show in a year and a half. Based on the contract, I thought Will would end the show after a ninety-minute set, but he just kept on strumming his banjo, kicking his kick drum and telling the audience how thankful and excited he was to play in front of people. Two and a half hours later, Will ended the show with the ballad There Is Hope For You.